Prelude: perspectives from a scientist

I don’t have many memories of my childhood in which I have not been drawing. I think I have always been drawing. When I was a teenager and transitioning from high school to university, my father told me that if I chose science as my career path, I could do still do art but if I chose art, I wouldn’t necessarily be able to do science. I wanted to be able to do science, though at that age I had no idea what exactly science academia was. I may have been culturally biased towards thinking that science was superior to art because Indian middle class families give far more value to having a socially approved career than following passions (unless of course you are passionate about engineering, medicine or law…then lucky you!) So, without worrying my teenage brain too much about the somewhat unaccepting nature of the field, I put away my aspirations of becoming an artist and started my journey in science. Today I analyze data from one of the rovers on Mars to understand the planet’s past water activity. I think it’s a great topic and to some extent my work as a researcher satisfies my urge to be creative, however I don’t think academia is a great environment to foster creative energy. I have often worked in teams and universities and found myself lost in the nebulous ‘personality’ of the teams. I have been terrified of voicing my opinions and of being myself because I felt like a kid who doodled in her notebooks in the back of the class and has now somehow ended up in a team that works with rovers on Mars. I didn’t pay much attention to the doodly kid who was able to visualize the bigger picture in her research and ask weird questions that led to interesting findings.

Art has helped me retain the idea of protecting my individuality, to ask questions that are uncommon in my field, and has helped me refrain from defining my self-worth based on critical evaluation of my research. Maybe I am lucky that I didn’t choose a path which would lead to my artwork being critically evaluated for the sake of my career. I view science as a less intimate part of my personality and feel less attached to it than I am to art which is why critical evaluation has a lower emotional impact. Emotional impact, as I have learned the hard way is a key component of motivation, although it is not given much importance and, in many fields, is looked down upon. Critical evaluation of my research has a significant impact on my motivation, but my field is not known for having established a system that can teach me how to feel at ease with garden-variety human emotions about work while staying focused, productive, and aware of the broader picture. I often wonder how organizations that involve so many human beings can be so disconnected from the reality of humanity. This is why I want to write about art. When I am impacted by critical evaluation of my scientific work, I rely on art to rediscover a sense of motivation for science. Especially the live arts because it helps me understand human systems from a third person perspective without getting caught up in the highs and lows of my specific role in my field.

Overcoming scientific and technical hurdles using novel ideas require a strong sense of individuality and understanding of the application of a specific problem-solving ability in a broad but often primarily human-based system. We don’t want to be doing the same things over and over again. We want to be solving new problems in better ways in a diverse team equipped with members with unique superpowers. When we keep single mindedly working on a niche project with similar sets of people for prolonged periods of time, we can lose sight of the bigger picture. If we fail to see the evolution of the problem and how our work fits into the large machinery that propels the system forward, it becomes easy to lose our sense of purpose and become demotivated. We need to understand that novel scientific and technological advances are a result of strategic human creativity. Often this understanding requires someone who can be an observer of all the little parts of a work system. This may be my best understanding of a curator. Someone who is a viewer of the machine without having any requirements to be a part of the machine. It is a very important role because without that external perspective, it often becomes hard to know the exact moment when the machine needs oiling or a part change or if the machine has become obsolete.

Live arts pieces are a great representation of human systems. The act of working towards attaining some sort of synchronicity to turn ideas into reality is somewhat analogous to work communities that are amalgamations of different personalities from diverse backgrounds trying to attain a unified goal. If people with unique skills are effectively assigned parts and places that they shine in, the performance dazzles. An existential awareness of each part and the machine as a whole is important at all stages to remain functional and relevant. Therefore, every system needs an observer who can create a narrative on how the parts fit into the machine and how the machine fits into the general system of a progressing society.

The process of live arts

Translation from artistic ideas to performance

For me, the live arts is a combination of human endeavors to express an idea through movement, voice, and incorporation of artistic tools in front of their audience in an ephemeral performance. It may be performed by an individual or by a group of people. One common aspect of the live arts is translation of creative thoughts into action and movement. In case of dance and music it requires understanding of human bodies, skill and practice. Larger the scale of the performance, more the amount of attention required for this translation because it will involve more variables i.e. more people, more material objects that require to be a certain way to be of service to the translation process of the artistic idea. Creative thinking has a certain air of unpredictability and the process of settling on an artistic idea can be somewhat chaotic in nature. Translation of creative thought into a presentable art piece is a marriage between chaos and order. All scales of art performances require a certain level of diligence to turn something creative into something presentable. This process deserves respect and recognition whether the artist is a novice or a prodigy because this is an essential part of the process for the birth of the art piece.

The performance

Live arts itself is the ephemeral period of interaction between the art and its viewers in that given time and space. This may be the reason why, to me, live arts feels more analogous to real human dynamics rather than a staged performance. In the moment of the performance, wherever it may be, the time and space become the gallery and the interaction between the art and the audience a part of the art. It is a unique experience that captures an unpretentious essence of being a part of a human system.

Translation from an art performance to a human story

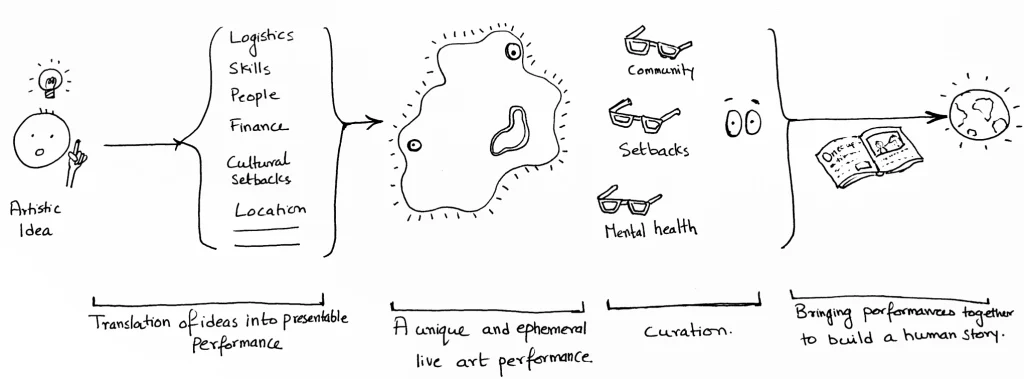

A single live art piece may shine by itself, however, it is but a set of stanzas in the poetry of humanity. Once juxtapositioned in a larger context, a single live arts piece can be a part of a story based on the lens the piece has been viewed through (as illustrated in Figure 1). The ensemble is just as much a part of the story as the live arts piece is. An observer who has witnessed the birth process of live arts despite its underlying setbacks, has the power to weave each unique thread of an art piece into a harmoniously colored tapestry representing human stories while adding deeper layers of meaning and richness. Our love of stories binds us together by helping us retain our cultural identities and heritage and by providing a platform for sharing common experiences and values. Curation is recognition of the unifying stories, creating a narrative that facilitates a thought process about these stories. These are the stories that inspire us no matter what career paths we decided to follow.

Why curate the live arts?

In this section I want to explore some things that we don’t instinctively think about when we are experiencing live arts. When we view art through lenses (summarized in Figure 1) that remind us of our social, political, physical, and mental limitations it may help us develop a kinder outlook towards the artistic process, the artists, and our communities. It may help us develop a richer and more meaningful interaction with our creative sides and with other members of our society. Here are some of the lenses to view art through that remind us what affects art, how are we affected by art, and how curation is a step forward:

Community

Live arts brings together people who are creative and people who are seeking creative inspiration. The platform of space and time in which live arts takes place is a blessed opportunity for all parties to find wellbeing and support in a community. It is an opportunity to pay respect to the artistic process and acknowledge that the translation of chaotic creative energy into organized artistic presentation is challenging. It is an opportunity to build a village where newer members of the community can find their footing and can receive guidance from mentors through thoughtful networking facilitated by curators. It is an opportunity for introducing unconventional methodologies and media, broadening artistic horizons and engaging diverse types of audience to new forms of art. It is an opportunity to focus intent on safeguarding and honoring the communities’ cultural heritage and to gain an openness and acceptance towards communities that are not familiar to us. Once we start viewing art though these lenses, art representing human systems can help us ask better questions about community policies, resource distribution, and our leaders. Thoughtful curation of performances that shed light on human systems can inspire us to see the larger picture of the current state of our community and help us be brave to ask the hard questions.

Setbacks

Artistic platforms are not universally leveled and policies in a country affect the individuality of artists, availability of artistic exhibition platforms, and the type of art. In some countries the government strongly oversees the type of art it is willing to sponsor (Takaguchi, 2018), in some, art is supported by commercialization (Irvine, 2013). Some countries cannot prioritize art when the citizens are in a state of struggle to preserve their constitutional rights (Grover, 2020; Schneider, 2020). The amount of art in a community may be a reflection of the state of social wellbeing. Having to fight for a livelihood or basic constitutional rights comes in the way of feeling a sense of safety that can enable creative thinking. So, if we look into a country’s socio-economic background, art pieces and performance may have been possible despite a troubled economic or political situation. If an art piece or performance is different from popular art, it has a story to tell. Perhaps a story that is of a community different than ours. A community that may be struggling and has new things to teach us about problems that we have not experienced yet. Kind curation of live arts pieces from diverse artists with different backgrounds can help us broaden our view of society, help us harness the strengths that unify us and help us learn tolerance towards differences that make us unique.

Mental health and social wellbeing

As I edit this article in March 2021, we have been socially distancing for over a year. We have been away from friends, colleagues, family, and loved ones. We have had to forgo traditions, festivals, and social events that brought us together and we have had to experience loss of human lives and livelihoods without the solace of being able to grieve with our village. It is incredibly hard to feel safe, productive, or balanced in a state of a global crisis. Our brains are going to retain the aftermath of this prolonged period of uncertainly and social isolation. We are going to have to accept that the definition of “normal life” has completely changed forever and we are going to have to understand the effects of this experience on our wellbeing.

Humans brains are hardwired to “feel” movement and emotions of other human beings (through something called mirror neurons: Di Pellegrino et al., 1992). We effectively communicate our needs, feelings, and stories through speech, facial expressions and movements and this entire ritual strengthens our sense of safety and wellbeing in a society. Being able to feel safe with other people is probably the single most important aspect of mental health and social support is the most powerful protection against becoming overwhelmed by stress and trauma (Van der Kolk, 2015). This is why we are drawn to stories. It is our way to feel connected with other human beings and feel safe and accepted by comparing our feelings, needs, and dreams. As we grow into adults, we exercise these rituals on many personal and professional levels to form meaningful relationships. For our love of stories, need for novel experiences, and for the need to connect with society we also exercise these rituals on a larger and a less personal scale when we do things like watch movies, attend concerts, and experience live arts performances. Watching a live arts performance is a great way to partake in the ritual of human connection through artistic expression. There is great value in this experience, and this may even be a vital social wellbeing technique following a global pandemic.

Trying to get through this altered sense of reality with our community may be one way of feeling safe again. Live arts is an avenue for us to connect with the community whether we are new members or veterans. Whether we are sharing our joy in celebration or sharing concerns and hardships during times of conflicts, differences, and difficulties. Engaging in artistic expression through movement and voice and connecting to this expression as an audience may be an effective social-scale coping mechanism which enables us to feel a sense of belonging and acceptance. Given the power of live arts as a social therapeutic process, art being produced during the pandemic is incredibly valuable and must be looked at with a renewed perspective. Creativity is challenging in a state of global crisis so all creative endeavors at this stage are not only precious but also play an important role in documenting a strenuous chapter in our communities’ story. Curating live arts to preserve this story is vital.

Takeaway

All human systems need a curator. Curation is the space for reflection about what we can do to make an existing system better, about how well are we aligned with our values, and if we are on track to attain our goals. Curation is an opportunity to watch ourselves grow. Problems in human systems are ever evolving so we need to have an open-minded approach that keeps us open to new solutions while staying grounded based on our limitations. Live arts is a key avenue to understand the nuances of human systems from a third person perspective which can initiate thought processes required for necessary changes in a field. Perhaps other fields (especially to my hope, science and academia) can draw inspiration from live arts to retain its humanity and the uniqueness of each of its members. I’ve summarized the process of an idea conception to curation and storytelling in Figure 1 which may be applicable to numerous human systems and act as a reminder to view our fields through various lenses with compassion, radical acceptance, and respect.

References

Di Pellegrino, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (1992). Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study. Experimental brain research, 91(1), 176-180.

Grover, Amitesh, 2020 https://www.hakara.in/amitesh-grover-3/

Irvine, M., 2013 “Cultural Hybridity: Remix and Dialogic Culture” https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/cctp-725-fall2013/

Schenider, T., 2020 https://news.artnet.com/opinion/gray-market-trump-arts-economy-1912905

Takiguchi, K., 2018. The Curating Nation. Curating Live Arts: Critical Perspectives, Essays, and Conversations on Theory and Practice, p.59.

Van der Kolk, B. A., 2015. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.